beCause CEO Nadine Hack at IMD Global Alumni event, Future of the Planet: Inspiring What Could Be – IMD President Jean-François Manzoni spoke of a more engaged response at board meetings when he talked about “doing well by doing good” than he’d received just a few months earlier when board members seemed to shrug it off as irrelevant. And we see something happening now

beCause CEO Nadine Hack at IMD Global Alumni event, Future of the Planet: Inspiring What Could Be – IMD President Jean-François Manzoni spoke of a more engaged response at board meetings when he talked about “doing well by doing good” than he’d received just a few months earlier when board members seemed to shrug it off as irrelevant. And we see something happening now

The Business Roundtable recently issued a statement redefining the Purpose of a Corporation in which they say we have to move away from exclusively shareholder primacy to a broader spectrum of stakeholders. And, at about the same time, Gillian Tett, US Managing Editor Financial Times, wrote Capitalism – a new dawn? addressing many of the same issues. Just recently she and the FT launched Moral Money, a series dedicated to explaining why investors should pay attention to environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles. I then had exchanges with Gillian and Paul Polman, who stepped down as CEO of Unilever and is launching IMAGINE to help companies pursue UN sustainability goals with a “collective sense of urgency,” especially to battle inequality & climate change.” We discussed why we believe we may have finally reached tipping point where corporations actually have to do something about corporate social responsibility, not just talk about it.

You can watch full video of presentation or see 2-min excerpt.

So, IMD asked me to share very specific stories rather than my general involvement in this sphere for the past five decades. I began in 1960s era of Rachel Carlson Silent Springs. Annika Falkengren, Managing Partner, Lombard Odier Group, referred to the 1992 Rio Climate Summit for which I helped organize the NGO Forum. I’ve been at this a long time. As this session that Susan Goldsworthy, IMD Professor, Leadership & Organizational Change, and I are sharing is, Understanding Urgency: Call for Leadership; Responsibility, Action, Hope, IMD wanted me to share two stories of hope to show that it can be done and it has been done.

First story: in the 1970s I helped four groups who at the time were bitter enemies – government leaders, community organizers, environmental activists and logger – come together to create what first became CA state legislation for renewable resources long before that term was in the common lexicon and then became the template for Global Green Plans in collaboration with Wangari Maathai. I even gave a TEDx, Adversaries to Allies, about it.

Our initial work was on reforestation. I had an “ah hah” moment that while it might feel cathartic for activists to chain themselves to trees to stop strip logging at a time when that was common, until they began to talk to those who were destroying the environment, nothing was going to change. So, I started to convene them because I knew the problem was too big for any one sector to address on their own. I knew if we had the hard conversations, together we could move the dial forward. So, even though motivations differed, they began an initially-wary coalition in which each group recognized that the capabilities of the other would strengthen each.

Through a process of intensive dialogue over time, we actually came up with a solution. I knew that unless these very disparate groups would engage with each other we never would find a solution. And, this is true about every problem we face: no one sector on its own has the skills set, resources, capacity, or knowledge base to solve any of the huge global problems we face. But, together, we actually do have the collective wisdom. Ultimately, we changed policies and practices from strip logging to a plan that for every one tree cut down, two were replanted.

Second story: which also involves a coalition of the initially not so willing partners. In 2000 global activists were protesting at AIDS conferences around the world with signs, “Coke kills workers in Africa.” Though Coca-Cola had the best policies in Africa for AIDS prevention, protection, testing and treatment of its workers, protesters demanded that they should provide the same services to its bottling affiliates, which were completely separate entities. Coke felt it could not justify that extra expenditure so they were at an impasse. They approached me saying they had a PR problem: I told them if they thought that they should go to Madison Avenue; but that, if they actually wanted to make changes by working with those opposing them to come up with a solution, I’d help them.

Again, we began a very intensive dialogue process: not easy to bring people who have absolutely conflicting ideas together. As I’m saying this, I’m realizing if you think of the incredibly divisive world we’re living in, if there was ever a need to bring together people with really different perspectives to have civil dialogue and find solutions, now more than ever we need this.

Coca-Cola began to realize was in its own enlightened self-interest to be serving its bottling affiliates’ employees: why, because if they became infected, especially the drivers, it would affect Coke’s entire supply chain. They also saw that the public didn’t distinguish Coke from its affiliates and activists were negatively impacting Coke’s brand. AIDS activists acknowledged that while they got media coverage for blasting Coke, their attack strategy was never going to change Coke’s policies. If they really wanted workers in Africa to stop dying, Coke would have to agree to transform. Ultimately, Coca-Cola provided AIDS services for bottling affiliates’ employees, starting with a pilot in seven nations and then expanding throughout the African continent with each stakeholder group paying some costs, including the company, the affiliates and employees. Even though the latter was nominal, I’ve learned that if you don’t put any “skin in the game” you’re not really a stakeholder.

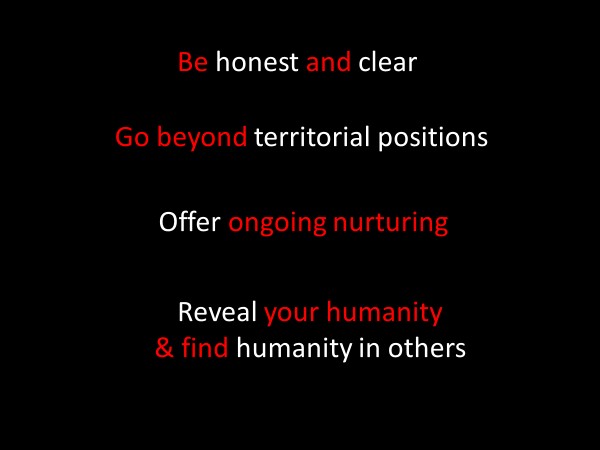

From these really difficult negotiations that involved a lot of complexity, I distilled important insights:

One: the starting point is that everyone has to be absolutely honest and clear about what they are willing to put into the collaboration and what they anticipate and desire to get out of it. This seems so obvious but I can’t even begin tell you the number of times I’ve seen partnerships fail because people simply weren’t really clear to each other – or even themselves – about their expectations.

Two: once the expectations are clear, you have to find and mobilize those who see a larger picture beyond territorial positions. Ideas and relationships are not finite: you can share them with others and no one is diminished; everyone is enhanced. We cannot afford the defensive mentality of “I gain my power but depriving you of what I have and I know.” It’s not a zero-sum game: it’s only together that we can achieve ambitious goals.

Three: Engagement is not a one-shot deal: it requires ongoing nurturing. None of this happens overnight. There were moments when each stakeholder was ready to walk away. But they stayed at it against all odds to overcome the obstacles. When there’s a breakdown, you have to step forward, own it and do what’s needed to regain the ruptured trust. It’s an iterative process of rebuilding bonds over and over.

Four: Essentially as human beings, while we come from different countries, different cultures, different regions, different perspectives, different ideologies, at core most human beings share the incredibly simple concerns. We all want our families to be healthy and happy; our communities and nations to be safe. To sustain dialogue with people who may be completely different and you may not agree with them, you have to show up with your whole self.

So, if you want to contribute at whatever level in whichever way to protect the future of our planet, while they seem deceptively simple, they’re actually very hard to do. This is leadership, responsibility and action that gives us hope.

So, if you want to contribute at whatever level in whichever way to protect the future of our planet, while they seem deceptively simple, they’re actually very hard to do. This is leadership, responsibility and action that gives us hope.

———-

Watch video of presentation or see 2-min excerpt. Nadine B Hack is CEO beCause Global Consulting, Senior Advisor Global Citizens Circle and a former IMD Executive-in-Residence. She frequently gives keynote addresses globally.